From Review to Action: Strengthening Digital Safeguarding in UK Universities After the DfE Report

by

Bec May

A new report from the Department for Education (DfE) has issued a stark message to Universities in England: step up efforts to keep students safe and reduce student suicide risk.

The report, which took almost two years to compile, examined 169 cases and outlined 19 urgent recommendations for the British higher education sector. These proposals rightly call for better care, greater access to mental health services, and safer student accommodations. Yet, how Universities are to bridge these crucial gaps in proactive safeguarding is left largely unaddressed, especially the role of technology in spotting digital distress signals.

This is where internet monitoring and reporting tools come in, bridging the gap between concern and action with real-time visibility.

The DfE Suicide report unpacked: What every university needs to know

The Department of Education’s 2025 report into student suicide is the most comprehensive review of its kind, examining 169 incidents across 73 UK higher education providers. The findings were both sobering and instructive:

107 suspected student suicide deaths and 62 incidents of non-fatal self-harm were reported in a single academic year. (2023-2024)

70% of the students were already known to university support services, yet many still fell through the cracks

47% had documented mental health difficulties; 31% had a formal diagnosis

38% were experiencing academic problems, and nearly a third showed patterns of disengagement

Almost one in four cases occurred in university-managed accommodation, and in several instances, serious incident reports noted missed opportunities to identify escalating risks.

The research is clear: staff had concerns. But existing systems failed to connect the dots.

Safeguarding in UK universities: No legal duties, but a moral imperative

Despite frequent references to a duty of care in university documentation, UK higher education institutions are not legally required to safeguard students’ well-being. This legal vacuum has led 25 bereaved families to petition Parliament for reform, calling for a statutory duty, similar to the Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSIE), which requires universities to exercise reasonable care in teaching and student support services.

Historically, universities acted in loco parentis, with legal protections aligning more closely to the needs of young people. However, since the legal age of adulthood was reduced from 21 to 18 in 1970, students entering university — often only weeks out of school — have found themselves without either the protections of childhood or the rights of employees, who are covered under workplace health and safety laws.

While some have argued that a statutory duty of care would demand unrealistic interventions, this needn’t be the case. A well-defined duty of care would exist to set clear, reasonable expectations, such as acting to prevent foreseeable harm. It need not involve constant monitoring as with KCSIE, but rather alerting for high-risk searches and online behaviours, and conducting risk assessment–driven ad hoc investigations when other wellbeing concerns are noted.

The goal is cultural: to empower staff to follow their instincts without fear of overstepping, and to establish clear lines of responsibility for student safety and well-being.

Whether this will become law yet remains to be seen. However, one thing remains clear: UK university students are at risk and need more consistent, compassionate, and coordinated systems of support. This means improving access to mental health services and equipping staff with the tools, data, and confidence to intervene early, before distress becomes a crisis.

Improving student safety and mental health: What the DfE recommends universities do now

The Department for Education’s review doesn’t just highlight failings — it sets out 19 specific recommendations to improve student safety across UK universities. From risk detection to coordinated support, these changes demand smarter systems and better data — the very gaps Fastvue is designed to fill.

Here’s a breakdown of the recommendations — and how Fastvue can help turn policy into practice

1–8: Training, Triage and Frontline Safeguarding

Mandatory training in mental health and suicide prevention for all student-facing staff.

Training must include risk recognition and neurodiversity, ensuring subtle or atypical distress signals are understood, both offline and online.

Academic decline equals risk. Struggling students should be flagged and supported, not left to fail quietly. Fastvue Reporter helps validate these concerns with digital behavioural data, such as stress-related search patterns.

Targeted support during high-pressure periods, such as exam time. Fastvue Reporter can help identify distress-related browsing during these windows, giving teams a heads-up before a crisis hits.

Review safety in university-managed accommodation, with improved welfare checks and better out-of-hours systems. Fastvue Reporter can monitor accommodation Wi-Fi networks to flag signs of late-night distress and high-risk searches, enabling welfare teams to spot issues even when no one knocks on the door.

Proactively reduce suicide cluster risk following a student death, using post-incident review and communication strategies.

Assess physical spaces after a suicide to prevent site romanticisation and improve safety.

Support those affected, for example, peers, flatmates, and tutors, with timely access to mental health services.

9–11: Breaking the Silos — Systems, Data and Communication

Expand access to support services, especially for high-risk groups (students facing financial, housing, relationship, or violence-related stress).

Improve internal communication across academic, wellbeing, and safeguarding teams — and upgrade IT systems to support this. Fastvue acts as a shared visibility layer between departments, ensuring concerns don’t stay stuck in silos.

Re-examine confidentiality practices, particularly in relation to safeguarding and data-sharing with accommodation providers. Fastvue’s triaged alert system supports privacy-conscious safeguarding, balancing the duty of care with respect for student dignity.

12–16: Incident Response and Accountability

Include families in serious incident investigations — not just out of courtesy, but as a core part of the process.

Ensure reviews are independently led, with findings properly recorded.

Professionalise incident investigations — no more ad hoc teams; use trained staff who understand youth suicide risk.

Require senior leadership sign-off, with a real commitment to acting on review outcomes.

Expand reviews to cover non-fatal self-harm, with students meaningfully involved where appropriate. Fastvue can contribute to post-incident reviews by providing objective digital context before and around the event.

17–19: Sector-Wide Reform and Long-Term Commitment

Introduce a duty of candour — universities must be transparent with families after a suspected suicide.

Create a national data forum to share suicide trends, patterns, and insights.

Make the national review ongoing, extend it UK-wide, and include serious self-harm cases, not just deaths.

| DfE Recommendation # | Safety Issue | Fastvue Role |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Staff training | Makes training actionable with real-time data |

| 3 | Academic struggles as a risk | Detects disengagement before formal flags |

| 4 | Calendar stress points | Flags increased digital distress during exams |

| 9 | Access to support | Reveals at-risk students who haven’t spoken up |

| 10 | Info sharing | Centralised visibility for cross-team coordination |

| 11 | Confidentiality | Respects privacy with human-reviewed reports and alerts sent only to the right people. |

| 14 | Serious incident review quality | Provides timeline/context for reviews |

| 15 | Leadership sign-off | Shows concrete evidence to prevent recurrence |

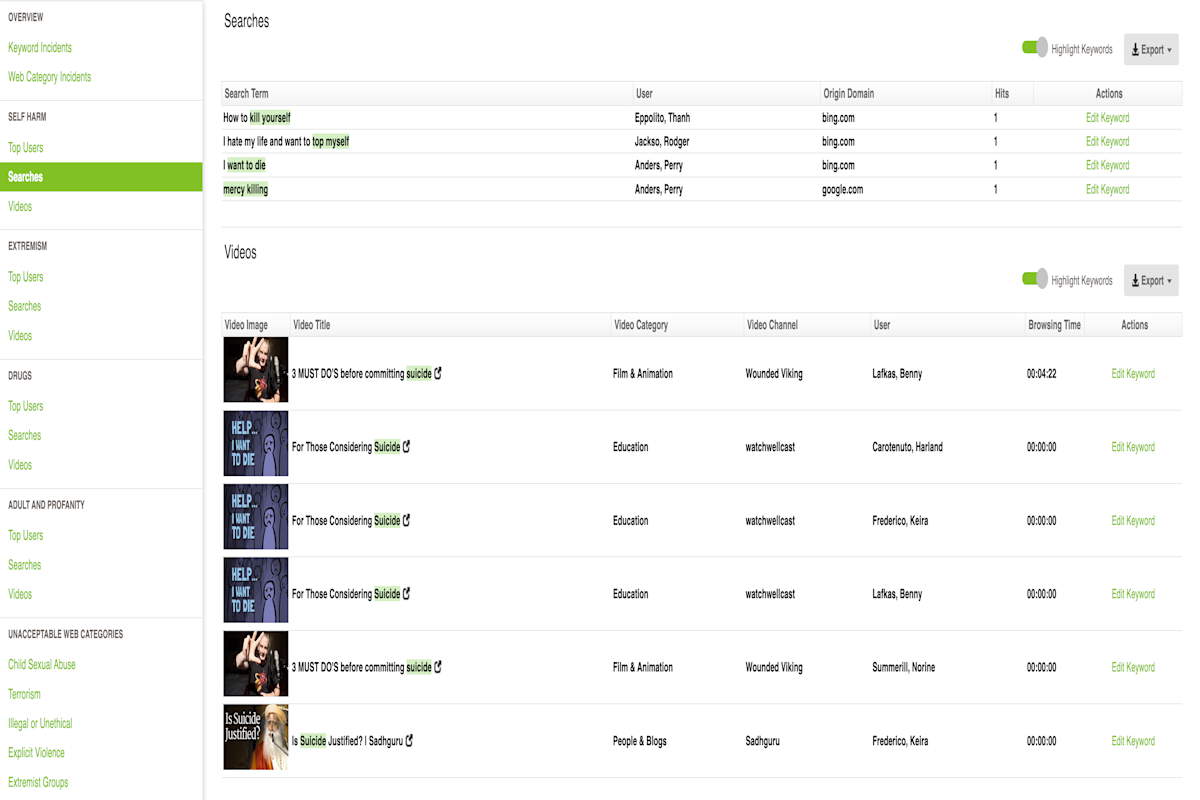

Flagging high-risk searches: how Fastvue detects digital distress

By monitoring web activity across campus networks, Fastvue can provide a vital early warning system for when students may be in crisis, especially when search activity points to emotional distress, sexual harassment, domestic abuse, or interest in dangerous content, or interest in dangerous content, rather than recovery or support.

Fastvue can flag a broad range of high-risk search terms commonly associated with suicidal ideation or self-harm. These include:

Explicit terms and phrases like ‘how to kill myself’, ‘ways to commit suicide’, or ‘cutting myself to feel better’

Indirect signals such as ‘I feel numb all the time’, ‘no one would miss me’, or searches related to overdosing on medication or other drugs and alcohol

Searches for forums and online communities where suicidal methods or ideation are discussed, like r/SuicideWatch, or suicide pacts

But it’s not just about the keywords. Fastvue can also be used to look at behavioural patterns, such as:

Sudden increases in late-night activity

A spike in emotionally charged or dangerous content consumption

Withdrawal from previous online engagement, gaming, or learning platforms

When these indicators surface, Fastvue can be configured to alert safeguarding teams immediately, enabling universities to intervene before a crisis unfolds.

This process is grounded in privacy-conscious risk assessment protocols: alerts are triaged by humans, outreach can be handled delicately, and student dignity is always preserved.

How to run ad-hoc investigations with Fastvue

With no statutory duty to monitor students continuously, Senior Leadership at forward-thinking Universities are starting to take a proactive, but respectful approach to safeguarding, especially when red flags begin to appear. Fastvue enables wellbeing officers and safeguarding leads to conduct focused, ad hoc investigations that support timely intervention for young people while maintaining student privacy.

Let’s take a look at a case study.

Case study: Disengagement and a drop in performance

A student’s academic performance has sharply declined. Attendance is patchy, coursework is missing, and tutors report multiple unanswered emails. It’s the kind of slow-burning concern that often goes unnoticed — or gets stuck in limbo between departments.

Recognising the pattern, the university’s wellbeing officer initiates an ad-hoc investigation using Fastvue Reporter.

The student is identified based on the academic referrals.

A targeted report is run on their recent network activity — no mass surveillance, just a focused snapshot.

The report reveals a surge in late-night searches about academic failure, burnout, and self-harm.

There’s also a sudden drop in engagement with the university’s virtual learning platform and communication tools.

Combined, the offline concerns and online signals paint a clear picture: this student is not just struggling — they’re in distress.

The wellbeing officer initiates contact through established support channels. The student is offered immediate help, and a care plan is implemented. Academic adjustments follow, alongside ongoing check-ins and support.

Fastvue didn’t diagnose the problem. But it surfaced the right information at the right time, so staff could act, not guess.

The need for integrated support systems in universities

One of the most urgent issues highlighted in the DfE report is the fragmentation within university systems. Academic departments, wellbeing services, IT, and safeguarding teams too often operate in silos, failing to share critical context that could change the outcome for a struggling student.

Fastvue bridges these gaps. By providing a centralised, real-time view of concerning online behaviour, Fastvue Reporter enables coordinated action across departments. A tutor noticing poor attendance or disengagement need no longer act in isolation; their concerns can be easily validated with accurate data from reports, and escalated appropriately.

While the law may not currently mandate digital safeguarding in higher education, the ethical responsibility to keep students safe is undeniable. Universities market themselves as guardians of student potential. That promise must extend beyond graduation statistics and league tables; it must include a commitment to student safety at UK Universities.

Ready to move away from crisis-only response?

It’s time to stop waiting for students to ask for help, or worse, for tragedy to force a review. Universities need systems that flag risk early, enable timely intervention, and support staff to act without second-guessing.

Fastvue won’t fix everything. But as part of a coordinated mental health and safeguarding strategy, it’s a damn good start.

See Fastvue in action

If your safeguarding plan doesn’t include digital signals, it’s incomplete. Let’s fix that. Book a live demo with our team of online safeguarding specialists and begin taking action before things spiral out of control.

Don't take our word for it. Try for yourself.

Download Fastvue Reporter and try it free for 14 days, or schedule a demo and we'll show you how it works.

- Share this storyfacebooktwitterlinkedIn